The New Ovarian Cancer Landscape: Many Questions, Much Hope

In the past 5 years, the FDA has awarded 4 drugs 9 new indications for the treatment of advanced ovarian cancers. Although these approvals represent a welcome expansion of the therapeutic toolkit for this challenging malignancy, the arrival of new options has outpaced efforts to discover the best use for each medication.

Elise C. Kohn, MD

Elise C. Kohn, MD

In the past 5 years, the FDA has awarded 4 drugs 9 new indications for the treatment of advanced ovarian cancers. Although these approvals represent a welcome expansion of the therapeutic toolkit for this challenging malignancy, the arrival of new options has outpaced efforts to discover the best use for each medication.

Should bevacizumab (Avastin), an angiogenesis inhibitor, be deployed against newly diagnosed cancers or held in reserve for recurrent tumors? Will patients who respond to 1 of the 3 recently approved PARP inhibitors later benefit from a second PARP inhibitor if they need a second course of treatment?

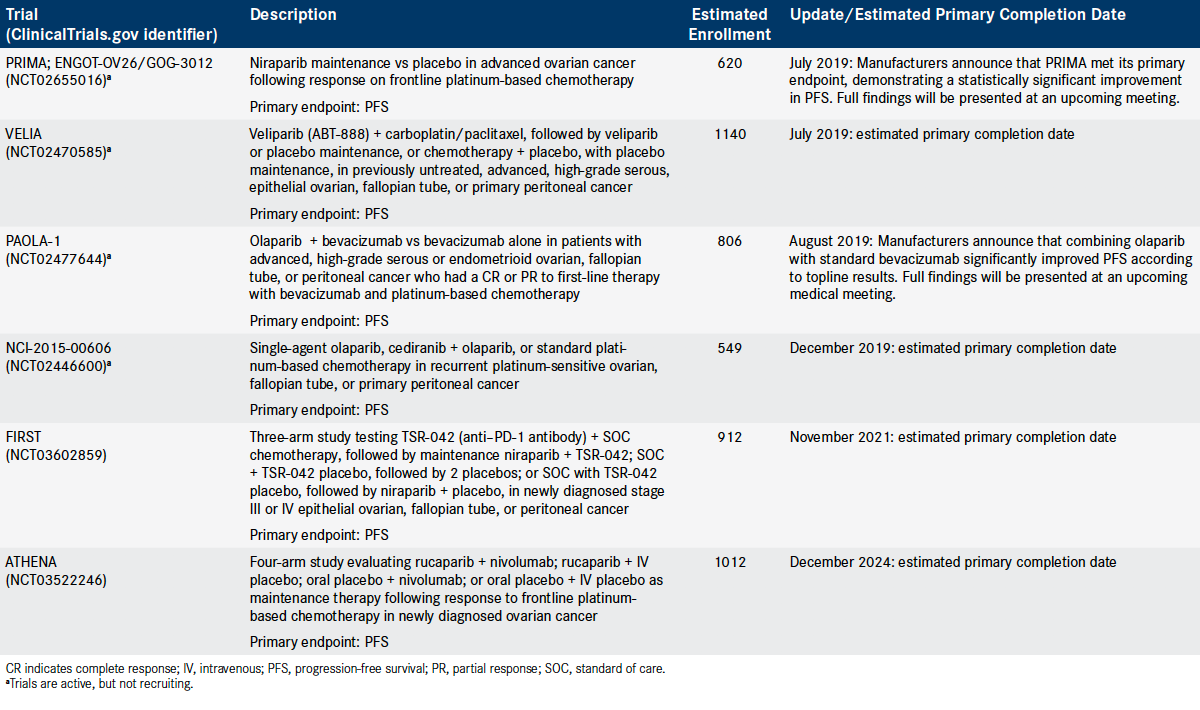

Investigators have yet to answer many such questions, and additional approvals may soon increase the complexity of optimizing treatments. New data may lead to expanded options for frontline maintenance therapy with the PARP inhibitors olaparib (Lynparza) and niraparib (Zejula), and late-stage trials of several combination therapies could spur more approvals (Table).

“The conundrum that we are now running into, with many PARP inhibitor approvals, is the question of where are PARP inhibitors best and most effectively applied for the women we serve, and I think the answer is that we don’t know,” Elise C. Kohn, MD, head of Gynecologic Cancer Therapeutics at the National Cancer Institute’s Clinical Investigations Branch, said in an interview with OncologyLive®.

“That makes treatment a challenge for physicians because they don’t know whether they should be using these treatments as primary treatments or in recurrent disease or whether they can just keep using PARP inhibitors in every setting,” she said. “There are studies underway to see if PARP inhibitors will produce responses more than once, but we have no data yet. There’s also the question of when to use bevacizumab. There is no question the drug works, but there’s no way to know when to use it or which patients will respond best because we have no predictive biomarkers for it.”

Although the new therapeutic options have added complexity to the field, they also have generated optimism. “I think the future is bright,” Elena S. Ratner, MD, said during a recent OncLive Peer Exchange® program on ovarian cancer where positive findings from several clinical trials were discussed.1 “I think just to even have this conversation and talk about these numbers, it’s not anything that we have been able to talk about previously.”

The emergence of PARP inhibitors, which are primarily approved for patients with BRCA mutations, underscores the need for molecular testing in patients with ovarian cancer, the Peer Exchange panelists stressed. “I’m excited…that all of us providers will take this responsibility to understand that we can no longer practice like it’s 2010,” said Ratner, an associate professor and co-chief of the section of gynecologic oncology at Yale University in New Haven, Connecticut. “The landscape is different. We understand the biology of ovarian cancer differently, and these tumors need to be studied and understood.”

Need for Improvement Persists

Outcomes for patients with ovarian cancer were improving even before the new drug approvals: The median overall survival (OS) from initial diagnosis rose from 34 months in 1983 to 52 months in 2012,2 and experts interviewed for this story said the recent FDA approvals have likely spurred further gains in broad survival statistics.

Table. Select Phase III Randomized Trials in Ovarian Cancer (Click to Enlarge)

Until the wave of new approvals, ovarian cancer was treated almost entirely by surgery and chemotherapy and, in some subtypes, radiation. Ovarian tumors have no gain-offunction oncogenes, so they did not present any obvious point of attack for new drugs.

“Classical high-grade serous ovarian cancer, which is the most common type and the biggest killer, is a disease of genomic instability. It has dominant oncogene mutations, but none of them are important enough to tumor function to make a great target,” Kohn said. “The best treatment strategy has been increasing the genomic instability and pushing the DNA damage far enough that you kill the cell. Chemotherapy does that directly, and PARP inhibitors do it indirectly by inhibiting DNA damage repair.”

Recent Drug Approvals

Bevacizumab

The timeline of new approvals in ovarian cancer begins in November 2014, when the FDA cleared bevacizumab for use in conjunction with any of 3 chemotherapies for women with recurrent platinum-resistant disease (Timeline).5-8

The approval was based on results from the phase III AURELIA study in 361 women with epithelial ovarian, primary peritoneal, or fallopian tube cancer.9 The women, who had received no more than 2 anticancer regimens prior to enrollment in the trial, were randomized to 1 of 6 treatment arms: paclitaxel, topotecan, or pegylated liposomal doxorubicin with or without bevacizumab. Bevacizumab plus chemotherapy decreased the risk of progression or death by 62% compared with chemotherapy alone. The median progression- free survival (PFS) was 6.8 months with bevacizumab versus 3.4 months with chemotherapy alone (HR, 0.38; P <.0001).9

In the AVF4095g trial, bevacizumab in combination with platinum-based chemotherapy increased the median PFS to 12.4 months versus 8.4 months with chemotherapy alone (HR, 0.46; 95% CI; 0.37-0.58; P <.0001) in patients with recurrent, platinum- sensitive disease.5

In June 2018, bevacizumab was approved in combination with carboplatin and paclitaxel, followed by bevacizumab as a single agent, for patients with stage III or IV disease following initial surgical resection. The decision was based on findings from the GOG-0218 study in which the use of initial and maintenance bevacizumab demonstrated a median PFS of 18.2 months compared with 12.0 months for chemotherapy alone (HR, 0.62; 95% CI, 0.52-0.75; P <.0001). In a third arm of the study, patients who received bevacizumab plus carboplatin and paclitaxel without the maintenance phase reached a median PFS of 12.8 months compared with 12.0 months chemotherapy alone, a difference that was not statistically significant.5

In the final analysis of GOG-0218, none of the 3 treatment arms resulted in a statistically significant gain in OS after a median follow-up of 102.9 months. However, in patients who started with stage IV disease, the use of concurrent-plus-maintenance bevacizumab with chemotherapy was associated with a longer median OS of 42.8 months versus 32.6 months with chemotherapy alone (HR, 0.75; 95% CI; 0.59-0.95).10

Notably, investigators also sequenced DNA from blood and tumor samples of 1195 of the 1873 patients enrolled in the study for germline and somatic mutations in BRCA1/2 and 14 other genes associated with homologous recombination deficiency (HRD).

The median OS was greater for patients with mutations in BRCA1/2 (61.2 months) or other HRD genes (56.2 months) than for those without mutations (42.1 months). Those findings translated into hazard ratios favoring a reduction in the risk of death of 0.62 (95% CI, 0.52- 0.73) for those with BRCA1/2 mutations and 0.65 (95% CI, 0.51-0.85) for HRD mutations.10

Although the results of the molecular analysis did not predict bevacizumab activity, they were prognostic, investigators concluded. “This has major implications for the design of future trials,” Tewari et al wrote. “… Unfortunately, many patients with ovarian cancer are not being tested for BRCA1/2. Strategies to optimize BRCA testing in affected populations and the development of a clinical platform for homologous recombination deficiency testing are implicit.”10

PARP Inhibitors

Bevacizumab inhibits microvascular growth and disease progression by binding to VEGF and preventing interaction receptors on the surface of endothelial cells.5 By contrast, PARP inhibitors block enzymes critical to cell damage repair; the class began emerging with the initial approval of olaparib in December 2014 and now includes niraparib and rucaparib (Rubraca).5-8 A fourth PARP inhibitor, talazoparib (Talzenna) is approved for patients with germline BRCA-mutated, HER2-negative locally advanced or metastatic breast cancer.

In ovarian cancer, all 3 inhibitors are approved as maintenance therapy following platinum-based chemotherapy in recurrent epithelial ovarian, fallopian tube, or primary peritoneal cancer.6-8 In some instances, the indications for olaparib and rucaparib specify that patients must have a germline or somatic BRCA mutation.6-8

The maintenance setting is important in the malignancy because most patients relapse after initial treatment with cytoreductive surgery and platinum- and taxane-based chemotherapy.10 All 3 PARP inhibitors were approved on the basis of PFS gains.

In SOLO-2, patients with germline BRCA mutations who received ≥2 prior platinum- containing chemotherapy regimens and were in complete response (CR) or partial response (PR) to the latest line of therapy were randomized to receive olaparib or placebo. Patients in the olaparib arm achieved a median PFS of 19.1 months compared with 5.5 months for placebo (HR, 0.30; 95% CI, 0.22-0.41; P <.0001).6

In the NOVA trial, patients in a similar patient population were randomized to receive either niraparib or placebo. For those with germline BRCA mutations, niraparib therapy resulted in a median PFS of 21.0 months compared with 5.5 months for placebo (HR, 0.26; 95% CI, 0.17-0.41; P <.0001). For those without germline BRCA mutations, niraparib also produced a benefit, with a median PFS of 9.3 months versus 3.9 months with placebo (HR, 0.45; 95% CI, 0.34-0.61; P <.0001).7

In ARIEL3, patients with recurrent ovarian cancer who were in response to platinum- based chemotherapy received either rucaparib or placebo. The median PFS was 10.8 months for patients who took rucaparib compared with 5.4 months for placebo (HR, 0.36; 95% CI, 0.30-0.45; P <.0001). Similar benefits were observed in patients with germline or somatic BRCA mutations and in a cohort of participants who were HRD positive, defined as the presence of a deleterious BRCA mutation or high genomic loss of heterozygosity.8

Potential New PARP Indications

Olaparib

Several new directors are possible for olaparib, as the first PARP inhibitor continues to register therapeutic milestones.

Findings presented at this year’s American Society of Clinical Oncology Annual Meeting (ASCO 2019) demonstrated that olaparib reduced the risk of disease progression or death by 38% versus chemotherapy in patients with platinum-sensitive, relapsed, germline BRCA1/2—mutated ovarian cancer who received at least 2 prior lines of chemotherapy.

In the phase III SOLO3 trial, the median PFS per independent review was 13.4 months with olaparib compared with 9.2 months with chemotherapy (HR, 0.62; 95% CI, 0.43-0.91; P = .013). Among all patients, the overall response rate by independent review was 72% with the PARP inhibitor compared with 51% with chemotherapy. The CR and PR rates were 9% versus 3% and 63% versus 49%, respectively.11

“SOLO3 is the first phase III randomized trial of a PARP inhibitor versus non—platinum-based chemotherapy in women with platinum-sensitive, relapsed, germline BRCA—mutated ovarian cancer,” said lead study author Richard T. Penson, MD, Massachusetts General Hospital.

Niraparib

Only about 15% of all patients with highrisk ovarian cancer have germline BRCA mutations that make them eligible for frontline olaparib maintenance therapy.12 For other patients, there is no approved option for introducing PARP inhibitors earlier in the treatment timeline, after first-line platinum-based therapy—but that may change soon.

In July, GlaxoSmithKline announced that its phase III PRIMA trial (NCT02655016) established PFS benefit, regardless of biomarker results, from niraparib maintenance therapy after surgery and platinum-based chemotherapy in women with newly diagnosed advanced ovarian cancer. Full findings, the company said, will be announced at an upcoming medical conference.13

Meanwhile, the FDA is considering a supplemental biologics license application for niraparib under its priority review program as a treatment for patients with advanced ovarian, fallopian tube, or primary peritoneal cancer who have been received ≥3 prior chemotherapy regimens and who have either a BRCA mutation or HRD and have progressed >6 months after their last platinum- based chemotherapy. The agency is expected to decide by October 24, 2019.14

Novel Combinations in the Works

Given that bevacizumab and at least 2 PARP inhibitors have been shown to extend PFS when paired with platinum-based chemotherapy in frontline therapy, investigators are testing whether the combination of platinum-based chemotherapy followed by both bevacizumab and a PARP inhibitor might do better.

In the PAOLA-1 trial (NCT02477644), the addition of olaparib to standard bevacizumab significantly improved PFS compared with bevacizumab alone as frontline maintenance therapy in women with advanced ovarian cancer, regardless of BRCA status, according to AstraZeneca and Merck, the codevelopers of olaparib.15

The study seeks to enroll 806 patients with newly diagnosed advanced stage III/ IV high-grade serous or endometrioid ovarian, fallopian tube, or peritoneal cancer, who reached a CR or PR to first-line therapy with bevacizumab and platinum-based chemotherapy. The companies said results from PAOLA-1 will be presented at an upcoming medical conference.15

Similarly, the combination of niraparib and bevacizumab is being explored. In the phase II ANANOVA trial, patients with previously treated high-grade serous/ endometrioid ovarian cancer who received niraparib plus bevacizumab had a median PFS of 11.9 months compared with 5.5 months for those who took niraparib alone (adjusted HR, 0.35; 95% CI, 0.21-0.57; P <.0001), according to findings presented at ASCO 2019.16 Plans call for a randomized phase III trial, NSGO-AVATAR, to compare the combination regimen with standard-of-care therapy, investigators said.

In another phase III trial, investigators are evaluating cediranib, which suppresses VEGF and tumor angiogenesis much like bevacizumab, in combination with olaparib in patients with recurrent, platinum-sensitive ovarian, fallopian tube, or primary peritoneal cancer (NCT02446600). The 3-arm study, which has an estimated enrollment of 549 patients, is randomizing participants to the combination therapy, olaparib monotherapy, or chemotherapy. The estimated primary completion date is December 2019.

In an updated analysis of a phase II study testing the combination in patients with platinum-sensitive, relapsed disease, the median PFS was prolonged among patients who received cediranib plus olaparib compared with olaparib alone (16.5 vs 8.2 months, respectively; HR, 0.50; P = .007). The benefit appeared to be driven by outcomes among patients without germline BRCA mutations, investigators noted.17

Immunotherapy

Investigators have tested immune checkpoint inhibitors (ICIs) as monotherapy for advanced ovarian cancers, but responses were disappointing, perhaps because ovarian cancers have a relatively low mutational burden and appear more like normal cells to the immune system than highly mutated tumors such as melanoma. Efforts to employ ICIs in the treatment of ovarian cancer have thus shifted to regimens that combine the ICIs with other treatment types.

The phase III FIRST study (NCT03602859), for example, will randomize 912 untreated women among chemotherapy and 2 placebos, chemotherapy plus niraparib plus placebo, and chemotherapy plus niraparib plus the anti—PD-1 drug TSR-042. The estimated primary completion data is November 2021.

The phase III ATHENA study (NCT03522246) will randomize 1012 women who respond to initial treatment with platinum-based chemotherapy to 1 of 4 arms of maintenance therapy: rucaparib plus nivolumab (Opdivo); rucaparib plus intravenous (IV) placebo; oral placebo plus nivolumab; and oral placebo plus IV placebo. The projected primary completion date is December 2024.

Chemotherapy

The spate of new approvals typically dominates ovarian cancer coverage, but treatment has been improving on other fronts as well. Don S. Dizon, MD, listed a growing trend toward giving some chemotherapy before surgery among the recent advances in ovarian cancer treatment that excited him the most.

“With chemotherapy before surgery, we are able to have stronger patients go to the operating room. There is a lesser chance that they are suffering from symptoms related to the disease. Resolving some of those symptoms and reducing the tumor burden makes for a better surgical outcome and better perioperative outcomes—that is, less blood loss, fewer days in the hospital, and less chance of dying in the immediate aftermath of surgery,” said Dizon, who is director of women’s cancers at Lifespan Cancer Institute and of medical oncology at Rhode Island Hospital in Providence.

“Although [trial results] do not show patients treated with neoadjuvant chemotherapy live longer than those who undergo primary surgery first [followed by chemotherapy], emerging options are showing there might be a way to improve outcomes, such as the use of heated intraperitoneal chemotherapy as an intraoperative treatment,” said Dizon, who also is a professor of medicine at Warren Alpert Medical School of Brown University, also in Providence. “One trial in Europe looked at this strategy in women treated with neoadjuvant chemotherapy and showed improved survival; other studies are ongoing to see if this is a consistent outcome.”

As enthusiastic as Dizon is about neoadjuvant chemotherapy, he also shares the general excitement about ongoing research that may soon create even more treatment options for patients with ovarian cancer.

Need for Screening

Bradley J. Monk, MD, FACOG, FACS, medical director for the US Oncology Research Network’s Gynecologic Program and a longtime leader in the ovarian cancer field, is among those who are looking forward to the next round of research findings.

“It’s all exciting,” Monk said in an interview. “I am exciting about moving PARP inhibitors beyond BRCA mutations in frontline therapy, and I am also excited about combinations.

“I’m particularly excited about the frontline PAOLA-1 study combining bevacizumab and PARP inhibitors because there may be some data coming out at ESMO,” he added, referring to the European Society for Medical Oncology 2019 Congress scheduled for September 27-October 1 in Barcelona, Spain.

For all the progress in treatment, however, Monk believes that the late diagnosis of most ovarian cancers means that finding a cure will be very difficult and that the best way to save lives is to prevent women from developing the cancer in the first place.

“There isn’t any diagnostic test on the horizon that will catch this early enough to remove it, but there are viable strategies for avoiding this,” said Monk, who also is professor and director of the Division of Gynecologic Oncology at Creighton University School of Medicine at St. Joseph’s Hospital and Medical Center in Phoenix, Arizona.

“Many [patients with ovarian cancer] are really [patients with fallopian tube cancer], so when a woman undergoes surgical sterilization, she shouldn’t have her tubes tied. She should have them removed and remove her risk of developing this cancer,” he said. “Also, women who know they have germline BRCA mutations—and all women should find out early if they do have BRCA mutations—should undergo risk-reducing salpingo-oophorectomy as soon as they are done having children.”

References

- Monk BJ, Moore KN, Ratner ES, Slomovitz BM. Shifting paradigms in ovarian cancer. OncLive® website. onclive.com/link/6236. Published June 25, 2019. Accessed August 26, 2019.

- Wu J, Sun H, Yang L, et al. Improved survival in ovarian cancer, with widening survival gaps of races and socioeconomic status: a period analysis, 1983-2012. J Cancer. 2018;9(19):3548-3556. doi: 10.7150/jca.26300.

- American Cancer Society. Cancer Facts & Figures 2019. Atlanta, GA: American Cancer Society; 2019. cancer.org/content/dam/cancer-org/research/cancer-facts-and-statistics/annual-cancer-facts-and-figures/2019/cancer-facts-and-figures-2019.pdf. Accessed August 26, 2019.

- Surveillance, Epidemiology, and End Results Program. Cancer stat facts: ovarian cancer. National Cancer Institute website. seer.cancer.gov/statfacts/html/ovary.html. Published April 2019. Accessed August 26, 2019.

- Avastin [prescribing information]. South San Francisco, CA: Genentech, Inc; 2019. www.accessdata.fda.gov/drugsatfda_docs/label/2019/125085s331lbl.pdf. Accessed August 26, 2019.

- Lynparza [prescribing information]. Wilmington, DE: AstraZeneca Pharmaceuticals; 2019. www.accessdata.fda.gov/drugsatfda_docs/label/2019/208558s009lbl.pdf. Accessed August 26, 2019.

- Zejula [prescribing information]. Waltham, MA; Tesaro, Inc; 2017. www.accessdata.fda.gov/drugsatfda_docs/label/2017/208447lbl.pdf. Accessed August 26, 2019.

- Rubraca [prescribing information]. Boulder, CO; Clovis Oncology, Inc; 2018. www.accessdata.fda.gov/drugsatfda_docs/label/2018/209115s003lbl.pdf. Accessed August 26, 2019.

- Bevacizumab solution in combination with paclitaxel. FDA website. bit.ly/33ZCsS9. Updated December 6, 2014. Accessed August 26, 2019.

- Tewari KS, Burger RA, Enserro D, et al. Final overall survival of a randomized trial of bevacizumab for primary treatment of ovarian cancer [published online June 19, 2019]. J Clin Oncol. doi: 10.1200/JCO.19.01009.

- Penson RT, Valencia RV, Cibula D, et al. Olaparib monotherapy versus (vs) chemotherapy for germline BRCA-mutated (gBRCAm) platinum-sensitive relapsed ovarian cancer (PSR OC) patients (pts): phase III SOLO3 trial. J Clin Oncol. 2019;37 (suppl; abstr 5506). meetinglibrary.asco.org/record/173435/abstract.

- Neff RT, Senter L, Salani R. BRCA mutation in ovarian cancer: testing, implications and treatment considerations. Ther Adv Med Oncol. 2017;9(8):519-531. doi: 10.1177/1758834017714993.

- GSK announces positive headline results in Phase 3 PRIMA study of ZEJULA (niraparib) for patients with ovarian cancer in the first line maintenance setting [press release]. London, UK: GlaxoSmithKline plc; July 15, 2019. bit.ly/2HtfFEO. Accessed August 15, 2019.

- U.S. Food and Drug Administration accepts GSK’s application for ZEJULA (niraparib) in late stage ovarian cancer with priority review [press release]. London, UK: GlaxoSmithKline plc; June 24, 2019. bit.ly/2Le2Alq. Accessed June 24, 2019.

- Lynparza phase III PAOLA-1 trial met primary endpoint as 1st-line maintenance treatment with bevacizumab for advanced ovarian cancer [press release]. Kenilworth, NJ: AstraZeneca and MSD Inc; August 14, 2019. bit.ly/2Z2endB. Accessed August 14, 2019.

- Mirza MR, Avall-Lundqvist E, Birrer MJ, et al. Combination of niraparib and bevacizumab versus niraparib alone as treatment of recurrent platinum-sensitive ovarian cancer: a randomized controlled chemotherapy-free study—NSGO-AVANOVA2/ENGOT-OV24. J Clin Oncol. 2019;37(suppl 15):5505. meetinglibrary.asco.org/record/173447/abstract.

- Liu JF, Barry WT, Birrer M, et al. Overall survival and updated progression-free survival outcomes in a randomized phase II study of combination cediranib and olaparib versus olaparib in relapsed platinum-sensitive ovarian cancer. Ann Oncol. 2019;30(4):551-557. doi: 10.1093/annonc/mdz018.

Nevertheless, the 5-year relative survival rate for ovarian cancer is only 47%, lower than most other cancer types, because a majority of patients (59%) receive a diagnosis of distant-stage disease, according to the American Cancer Society’s Cancer Facts & Figures report for 2019. Five-year survival is twice as high in women younger than age 65 years (60%) as in those 65 and older (30%); however, the median age at diagnosis is 63 years.3,4