Exploring the Role of BTK Inhibitors in B-Cell Lymphomas

During an OncLive® Scientific Interchange, community and academic oncologists review the current treatment landscape and evaluate therapeutic strategies involving BTK inhibitors in B-cell lymphomas.

Constantine S. Tam, MD, the Peter MacCallum Cancer Centr

Constantine S. Tam, MD

On December 5, 2019, an OncLive® Scientific Interchange, “Bruton Tyrosine Kinase Inhibitors in B-Cell Lymphomas” took place in Orlando, Florida. The goal of the interchange, facilitated by Constantine S. Tam, MBBS, MD, an associate professor of hematology from the Peter MacCallum Cancer Centre at the University of Melbourne, Australia, was to review the current treatment landscape and evaluate therapeutic strategies involving Bruton tyrosine kinase (BTK) inhibitors in B-cell lymphomas. Community and academic oncologists at the Scientific Interchange discussed emerging data that were presented at the 2019 American Society of Hematology (ASH) Annual Meeting and Exposition, including how these data on efficacy and relative safety profiles of the FDA-approved BTK inhibitors may reflect real-world practice patterns.

Important data from the 2019 ASH Annual Meeting and Exposition and points of discussion from the Scientific Interchange are highlighted within this article, including expert insight on how novel regimens and ongoing clinical trials may impact the treatment landscape.

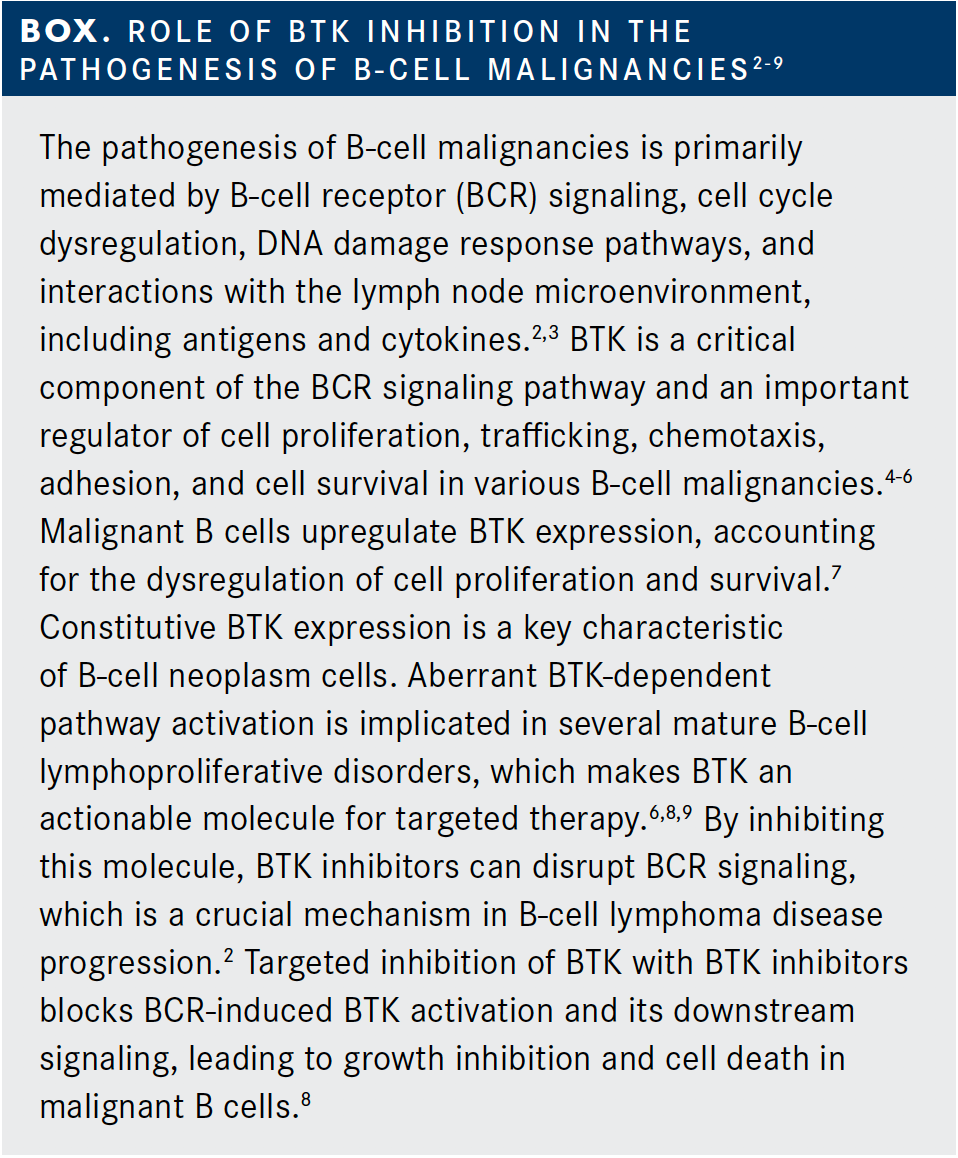

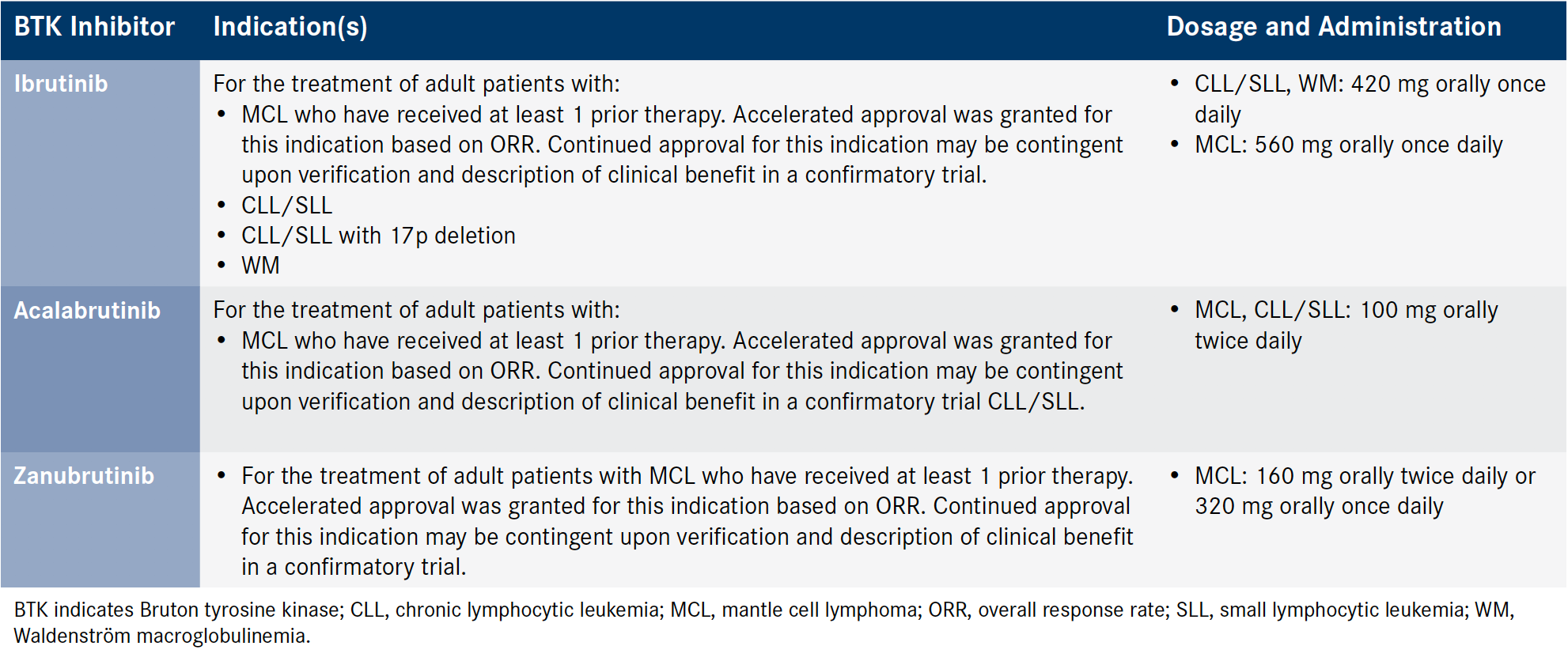

B-cell lymphomas, such as chronic lymphocytic leukemia (CLL), mantle cell lymphoma (MCL), and Waldenström macroglobulinemia (WM), are mature B-cell neoplasms, each having unique clinical presentations requiring different therapeutic strategies.1 Previous treatment options, including chemotherapy, radiotherapy, or immunotherapy, alone or in combination, often were associated with dismal prognoses. The advent of BTK inhibitors has revolutionized the treatment of B-cell lymphomas.2 Please refer to the Box for an overview of B-cell pathogenesis and the role of BTK inhibition.2-9 BTK inhibitors with indications across B-cell neoplasms have the potential to benefit more patients and to generate better outcomes by complementing or replacing previous treatment options.10 As shown in the Table, there are 3 FDA-approved BTK inhibitors—ibrutinib, acalabrutinib, and zanubrutinib—and several additional agents that are under investigation in ongoing clinical trials.11-14

As the therapeutic landscape continues to evolve, identifying treatment regimens that optimally align with individual patient profiles are essential. As targeted therapies, BTK inhibitors offer an option for precision medicine and a potentially lower toxicity profile than that of their chemotherapeutic counterparts. This article reviews clinical developments of BTK inhibitors in the CLL, MCL, and WM treatment landscape, including clinical efficacy and safety data presented at the 2019 ASH Annual Meeting and Exposition that were further discussed at the scientific interchange, as well as practical considerations and usage in the clinical setting.

Current Clinical Developments of BTK Inhibitors and Real-World Insights Into the Treatment of CLL/SLL

The treatment landscape of CLL and small lymphocytic lymphoma (SLL) has dramatically changed, in part because of the development and approval of BTK inhibitors. Faculty at the scientific interchange discussed key results of recently presented clinical trial results and emphasized their use of BTK inhibitors in the clinical setting.

Frontline Therapy Selection

Combination treatment with a Bcl-2 inhibitor, venetoclax, and an anti-CD20 monoclonal antibody, obinutuzumab, was cited as the preferred frontline therapy for CLL. Jean Koff, MD, MS, an assistant professor in the Department of Hematology and Medical Oncology at Emory University School of Medicine, said that selection of Bcl-2 combination therapy in frontline treatment of CLL is based on efficacy results that “are very, very promising in terms of long-term disease control, depth of remission, and of course time-limited therapy.” Nadia Khan, MD, an assistant professor in the Department of Hematology and Oncology, Fox Chase Cancer Center, agreed that the combination “is time-limited, and a lot of patients will be able to come off treatment for a long period of time.” Notably, the selection of frontline CLL treatment therapy may differ among institutions. Although this combination is used in large academic and community centers, faculty indicated that there are disparities in uptake of emerging treatment strategies; rural clinics continue to use BTK inhibitors, such as ibrutinib, for instance. BTK inhibitors may still be considered a viable treatment alternative in the frontline setting for fragile patient populations, such as those with a high burden of disease, given the increased risk of tumor lysis syndrome associated with Bcl-2 therapy.

Ibrutinib

Results from the extended follow-up of the phase III RESONATE- 2 and RESONATE trials were presented at the 2019 ASH Annual Meeting and Exposition, and they showed the safety and efficacy of ibrutinib in the first-line and subsequent settings for patients with CLL or SLL.15,16 During the discussion of the results, faculty at the scientific interchange noted that ibrutinib is rarely used as frontline therapy; however, ibrutinib is often selected for the treatment of relapsed or refractory (R/R) CLL or SLL.

Click to Enlarge

Table. FDA-Approved Indications and Recommended Dosing of BTK Inhibitors11-13 (Click to Enlarge)

Based on these results and real-world experience, ibrutinib should be used with caution in patients with, or at risk, of atrial fibrillation. Jacqueline Barrientos, MD, MS, an associate professor of hematology and oncology at Feinstein Institute for Medical Research, said that if she is “very concerned” about atrial fibrillation yet wants to use a BTK inhibitor, she “chooses acalabrutinib.” Likewise, William Donnellan, MD, the director of leukemia/myelodysplastic syndrome research at Sarah Cannon Research Institute, prefers using acalabrutinib over ibrutinib therapy in patients with chronic atrial fibrillation. For patients with atrial fibrillation requiring anticoagulation, if their only exposure had been ibrutinib, Brad Kahl, MD, a professor of oncology at Washington University School of Medicine, said he “would probably switch to venetoclax because…acalabrutinib increases bleeding risk.” Donnellan stated that switching between BTK inhibitors or other therapy in cases of patients with atrial fibrillation depends on the patient’s risk of bleeding and arrythmia severity. He sometimes chooses to keep lower-risk patients on ibrutinib. Attendees noted that caution must be taken when switching therapies to prevent accelerated CLL progression or flares. Donnellan and Barrientos always overlap when switching therapies; in contrast, William Wierda, MD, PhD, an assistant professor of medicine in the Department of Leukemia at the MD Anderson Cancer Center, does not overlap therapies.

The hypertension associated with ibrutinib can be difficult to control, and management approaches include discontinuing treatment, switching to another agent, and antihypertensive therapy. Khan has more experience addressing hypertension in patients taking ibrutinib than in those taking acalabrutinib, and she stated that she sees hypertension “fairly commonly in elderly patients who are already on a number of antihypertensives. We reduce in some cases; it depends on how long patients have been on the therapy. In some cases, we will stop therapy for a period of time until the blood pressure is controlled before resuming therapy, but [we could also] switch to acalabrutinib.”

Another AE associated with ibrutinib is serious infection. One study showed that of 378 patients with B-cell lymphomas, 11.4% developed invasive bacterial or invasive fungal infections within a median time of 136 days following ibrutinib initiation.17 “Blastomycosis, cryptococcus, and strange unusual flares of infection [can appear], particularly when patients are getting started on treatment” with ibrutinib, according to Wierda. Protozoal infections can also occur. Prophylactic or therapeutic treatments for infections associated with ibrutinib include acyclovir, trimethoprim/sulfamethoxazole (pneumocystis pneumonia prophylaxis), and antifungals. Some attendees stated that their center does not use any infection prophylaxis, while others shared that they administer prophylactic treatment for infections to high-risk patients, such as those with transplants, a history of shingles, or recurrent pneumonias. Other ibrutinib-related toxicities include arthralgias and myalgias, diarrhea, cytopenia, and dermal toxicity. According to Khan, joint and muscle pain can be treated with nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs or even steroids. Tam stated that diarrhea typically occurs at ibrutinib initiation and will usually resolve spontaneously without issue. For cytopenia, Tam gives granulocyte colony-stimulating factor, and Wierda typically sees it resolve on its own as patients improve with ibrutinib. Regarding dermal toxicity, Kahl has had to discontinue ibrutinib for some patients because she could not control the related symptoms. “Quite a few patients get a lot of cracking of their fingertips, which [can be] very painful, and paronychia on their nails. Or [patients] get little ulcerations around their lips or their nose,” she said. For other patients with obesity, ibrutinib challenged the management of chronic lower extremity swelling, Kahl noted, “to the point where [I] eventually just had to stop [ibrutinib].” Neither Kahl nor Wierda have experienced those types of AEs with acalabrutinib.

As noted by the attendees, other BTK inhibitors, based on their safety profiles, may be more appropriate therapies than ibrutinib for certain patients. Studies have demonstrated that both of the second-generation BTK inhibitors, acalabrutinib and zanubrutinib, have relatively lower rates of common toxicities (including diarrhea, fatigue, nausea, and headache), and in some cases, decreased hematologic toxicities (neutropenia and thrombocytopenia).11-13,18

Acalabrutinib

Acalabrutinib was approved in 2019 as initial or subsequent therapy in adults with CLL or SLL. It is a small molecule irreversible BTK inhibitor like ibrutinib, but it displays less off-target kinase inhibition of EGFR and interleukin 2—inducible T-cell kinase.12,18,19 The therapy was approved based on the clinical efficacy and safety demonstrated within the phase III ELEVATE-TN and ASCEND clinical trials. Because of these combined findings, acalabrutinib monotherapy for patients with R/R CLL has been added as a first-line, category 1 therapy in the most recent National Comprehensive Cancer Network guidelines.20

Evidence supporting acalabrutinib in the first-line setting was presented at the 2019 ASH Annual Meeting and Exposition. ELEVATE-TN was an open-label, randomized, multicenter phase III trial evaluating the safety and efficacy of acalabrutinib as a monotherapy (n = 179) or acalabrutinib in combination with obinutuzumab (n = 179) compared with chlorambucil plus obinutuzumab (n = 177) in previously untreated patients with CLL.21 At a median follow-up of 28.3 months, the primary end point of independent review committee (IRC)-assessed PFS was not reached by patients in both acalabrutinib treatment arms, compared with a median PFS of 22.6 months with chlorambucil/obinutuzumab. Patients treated with acalabrutinib/obinutuzumab achieved a 90% reduction in the risk of disease progression or death compared with those who received chlorambucil/obinutuzumab (HR, 0.10; 95% CI, 0.06-0.17; P <.0001).21 The rates of specific AEs of clinical interest of any grade for acalabrutinib/obinutuzumab, acalabrutinib monotherapy, and chlorambucil/ obinutuzumab were atrial fibrillation (3.4% vs 3.9% vs 0%), hypertension (7.3% vs 4.5% vs 3.6%), major bleeding (2.8% vs 1.7% vs 1.2%), infections (69.1% vs 65.4% vs 43.8%), and second primary malignancies, excluding nonmelanoma skin cancer (NMSC) (5.6% vs 2.8% vs 1.8%).21

Faculty also discussed results of the ASCEND trial, a randomized, global, multicenter, open-label, phase III trial that evaluated the efficacy and safety of acalabrutinib in the R/R setting. A total of 310 patients with R/R CLL were randomized 1:1 to receive either 100 mg of acalabrutinib monotherapy twice daily or rituximab in combination with physician’s choice of idelalisib or bendamustine.22 At a median follow-up of 16.1 months, acalabrutinib significantly prolonged PFS compared with the comparator arm (median not reached vs 16.5 months); patients treated with acalabrutinib experienced a 69% reduction in risk of progression or death (HR, 0.31; 95% CI, 0.20-0.49; P <.0001). The IRC-assessed overall response rates (ORRs) did not significantly differ between the acalabrutinib arm and the 2 other cohorts (81% vs 75%).22 Within the acalabrutinib and comparator arms, respectively, the AEs of interest were atrial fibrillation (5.2% vs 3.3%), major hemorrhage (1.9% vs 2.6%), grade 3 or higher infections (15% vs 24%), and secondary primary malignancies, excluding NMSC (6.5% vs 2.6%).22

Within the discussion at the scientific interchange, faculty noted that the recent trial data and approval of acalabrutinib for CLL or SLL influenced treatment decisions within the oncology community. Faculty noted that ibrutinib and acalabrutinib have comparable efficacy in CLL; however, acalabrutinib is preferred over ibrutinib in frontline treatment due to the better tolerability confirmed by personal experience and in clinical trial settings. Tam noted that he has observed clinicians selecting acalabrutinib over ibrutinib “based on [AEs] rather than efficacy.” In his practice, Tam cited that acalabrutinib is “a lot easier to use [than ibrutinib]. The rash is not there. The nail changes are not there and the atrial fibrillation seems slower.” Acalabrutinib may be an option for patients who are intolerant to ibrutinib or for patients with conditions of special interest. Khan noted that the decision for acalabrutinib use as frontline therapy would depend on the comorbidities of the patient. For example, several faculty members noted that they would select acalabrutnib for patients who had difficulty managing hypertension and those with a history of atrial fibrillation.

Zanubrutinib

Zanubrutinib may provide an alternative to ibrutinib. It is more selective, characterized by a lower-toxicity profile, and is currently undergoing clinical trial investigation for patients with CLL and SLL in the first-line, relapsed, and refractory settings. Faculty at the scientific interchange discussed updates from the phase III SEQUOIA (BGB-3111-304) and ALPINE trials and the phase I/II AU-003 study that were presented at the 2019 ASH Annual Meeting and Exposition.11,23,24

Results from a median 7-month follow-up interim analysis of arm C of the open-label, multicenter SEQUOIA trial demonstrated the efficacy and safety of zanubrutinib in patients with treatment-naive CLL or SLL with del(17p). Of the total patient population in arm C (N = 109), 75.6% of patients achieved a partial response ([PR] n = 68) and 15% of patients achieved a PR with lymphocytosis (n = 16). The ORR was 92.2% (95% CI, 84.6%-96.8%). In the safety analysis, zanubrutinib was shown to be well tolerated, and the toxicity profile was consistent with previously published AEs. Overall, 33 patients experienced grade 3 or higher AEs, the most common of which were neutropenia (n = 10), pneumonia (n = 2), and hypertension (n = 2).23

Results of the AU-003 and ALPINE clinical trials on zanubrutinib were also presented at the 2019 ASH Annual Meeting and Exposition. Updated results of the open-label, multicenter, phase I/II AU-003 trial, after a median follow-up of 25.1 months, were presented. The results were specific to the cohort of patients with CLL or SLL with no previous BTK therapy, grouped by treatment-naïve and R/R status. Of the patients overall (N = 122), 14.2% achieved a complete response [(CR] n = 17), 74.2% achieved a PR (n = 89), and 7.5% of patients achieved a PR with lymphocytosis (n = 9). The ORR was 97%, and the PFS rate at 2 years was 89%. The grade 3 or higher AEs experienced by more than 5% of the patients were neutropenia (14%), pneumonia (6%), and anemia (6%).24

The ALPINE trial randomized patients 1:1 to ibrutinib or zanubrutinib in relapsed refractory CLL and is now fully accrued. The estimated primary completion date is February 2021. “Instead of going for a PFS end point, which would be forever,” said Tam, “they went for an overall response end point.” He deemed ALPINE to be an “incredibly brave” study. Koff agreed, saying that the study “will move the needle forward in a significant way to see whether ORR, which is their end point, is different. That could make more people reach for zanubrutinib because we’ll have definitive data. [However,] long-term data are what will push [my] practice toward one or the other.”

Regarding the SEQUOIA arm C data, Tam stated that final conclusions cannot yet be drawn “apart from the fact that the drug works so far.” However, it appears that the AE profile of zanubrutinib is similar to that of acalabrutinib, including low rates of atrial fibrillation and bleeding. This similarity exists although the development of the 2 drugs “went in different directions. Acalabrutinib [was developed at] the lowest dose that was effective to minimize [AEs], whereas the zanubrutinib dose [was] pushed to the highest possible for efficacy,” noted Tam. For a drug “8 to 10 times the dosage of an ibrutinib equivalent, the [AE] profile looks pretty good,” he said. He mentioned that currently, no cases of atrial fibrillation with zanubrutinib have been documented, and the therapy “seems to be nicer than ibrutinib across most settings….Patients don’t feel well on ibrutinib, and we don’t get as much of a complaint on zanubrutinib. Having said that, I think the bleeding is real….Although the overall bleeding rates seem slower [on zanubrutinib], we still get the occasional patients who have severe bleeding [on that therapy]. And I don’t believe that acalabrutinib is free of bleeding.” Zanubrutinib is also not associated with the headaches that Tam said “are unique to acalabrutinib.”

Real-world evidence has demonstrated that BTK inhibitors can serve as salvage therapy and offer substantial PFS. Faculty noted that BTK inhibitors may be best for the treatment of patients with CLL in the R/R setting who demonstrate resistance or intolerance to venetoclax. Depending on the duration of response (DOR), Khan noted that she would potentially consider treating with a BTK inhibitor at relapse or reinitiating venetoclax. Additional novel treatments are still needed to address ongoing challenges, such as Richter transformation in CLL, clonal evolution, immune dysfunction in remission, or continued progression, according to Donnellan: “Despite all the new agents, we still have patients who are progressing.”

Exploring the Treatment Landscape and Role of BTK Inhibitors in Mantle Cell Lymphoma

Until about 5 years ago, the treatment of MCL consisted mainly of intensive chemotherapy or stem cell transplant consolidation therapy. These options were usually limited to younger and more physically fit patients. However, the introduction of BTK inhibitors and other nonchemotherapeutic options have completely changed the treatment paradigm of MCL.3 Ibrutinib, acalabrutinib, and zanubrutinib are approved for the treatment of patients with R/R MCL who have received at least 1 prior therapy.11-13

Ibrutinib

In a presentation at the 2019 ASH Annual Meeting and Exposition, long-term follow-up pooled data from 3 clinical trials—SPARK (NCT01599949), RAY (NCT01646021), and PCYC-1104 (NCT01236391)—demonstrated an overall favorable outcome of the use of ibrutinib in patients who either relapsed early after frontline treatment or who had durable frontline remission.25 All patients enrolled (N = 370) in the 3 trials had R/R MCL and received ibrutinib 560 mg once daily until disease progression or development of unacceptable toxicities. The results, Tam pointed out, demonstrated that ibrutinib use in the first relapse of MCL is “much better than in later lines [of therapy], in terms of complete remission and progression-free survival.” In the 3.5-year follow-up, the study population with 1 line of prior therapy (n = 99) achieved a median PFS of 25.4 months (95% CI, 17.5-57.5) compared with a median PFS of 10.3 months (95% CI, 8.1- 12.5) in patients with more than 1 line of therapy (n = 271). Low discontinuation rates were also reported, which Tam proposed were due to ibrutinib as the sole treatment for this indication at the time. With follow-up for as long as 92 months (median, 41 months), 11.9% of patients discontinued ibrutinib due to AEs.25 Tam noted, “When these studies were carried out, there were really no other treatment options for these patients, so they just [continued on the study].”

Acalabrutinib

Acalabrutinib was approved for R/R MCL in 2017, and faculty said that acalabrutinib is preferred as frontline therapy in R/R MCL based on higher response rates, the most CRs, and a slightly longer PFS compared with ibrutinib. Kahl noted that a few patient factors guide treatment selection: “If [patients with R/R MCL are] okay with taking a twice-a-day pill, and if they are not on a proton pump inhibitor, or if they can do something else for their reflux, then I prefer acalabrutinib.” Considering that the median age for MCL diagnosis is approximately 70 years, and considering acalabrutinib’s safety profile, Craig Sauter, MD, clinical director of the Adult Bone Marrow Transplant Service at Memorial Sloan Kettering Cancer Center, believes the therapy will continue to gain more traction.

ACE-LY-004 was a pivotal study that accelerated the FDA approval of acalabrutinib treatment in R/R MCL. This open-label phase II trial included 124 patients with R/R MCL who received oral acalabrutinib at 100 mg twice per day for 11 months. At a median follow-up of 15.2 months, results showed an ORR of 81% and a CR of 40%. Although the CR rate was relatively high, Tam recommended caution in interpreting this result. “The CR is probably overestimated because [the study used] PET [positron emission tomography] scans,” he said. Tam explained that ibrutinib studies on BTK inhibitors for R/R MCL used CT scans, and patients with residual masses were not considered to have a CR. The ACE-LY-004 study used PET scans, and patients with residual masses could nonetheless be categorized as PET negative and be considered to have a CR.26

Zanubrutinib

In 2019, the FDA provided an accelerated approval for zanubrutinib for R/R MCL based on its efficacy and safety demonstrated in the BGB-3111-AU-003 and BGB-3111-206 studies.11

BGB-3111-AU-003 was a phase I/II, open-label, doseescalation, single-arm trial; it included 32 previously treated patients with MCL who had received at least 1 prior therapy. Patients received zanubrutinib either 160 mg twice daily or 320 mg daily. The ORR was 84% (95% CI, 67%-95%). The percentages of patients achieving CRs and PRs were 22% and 62%, respectively. Patients achieved a median DOR of 18.5 months (95% CI, 12.6 to not evaluable).11 BGB-3111-206 was a phase II, open-label, multicenter, single-arm trial that included 86 patients with MCL who had received at least 1 prior therapy. Zanubrutinib was given at 160 mg orally twice daily until disease progression or unacceptable toxicity. The results showed an ORR of 84% (95% CI, 74%-91%); CRs and PRs were achieved by 59% and 24% of patients, respectively. At 24 weeks, the PFS was an estimated 82%. Patients achieved a median DOR of 19.5 months (95% CI, 16.6 to not evaluable).11 The key finding, “the headline result,” of this trial, according to Tam, “is the CR rate of 59% in a study that exclusively used PET scan to restage patients.”27 The PFS results were “difficult to interpret because the follow-up of the study is so short,” he stated. “For this study, I would like to see a PFS that holds up [after] another couple of years of follow-up. [At this point, zanubrutinib] looks a little better than ibrutinib, but it doesn’t look like a home run.”

Tam noted that no atrial fibrillation occurred.11 Of the 118 patients with MCL treated with zanubrutinib across both trials, the most frequent events were pneumonia (11%) and hemorrhage (5%). Faculty noted that the current data on zanubrutinib do not sway them from their current regimen of acalabrutinib for R/R MCL. “Toxicity-wise, I’m not sure we’re seeing any major differences [between acalabrutinib and zanubrutinib],” said Koff. However, attendees stated that they would be interested in gaining experience with zanubrutinib in their practices.

Although acalabrutinib and zanubrutinib may be better than ibrutinib based on response rate, PFS, AE profile, and tolerance, an unmet need still exists for novel therapies that can address patients with MCL who fail BTK inhibition. These patients can be “very hard to manage,” according to Donnellan. Venetoclax is often used first for these patients, because “there is nothing else to use,” said Tam. He noted disappointment in venetoclax “in terms of durability post BTK inhibition.” Another challenging patient population to manage are those with a TP53 mutation, which is a mutation in MCL associated with more aggressive disease and worse outcomes. Attendees stated that their treatment for these patients can involve giving a BTK inhibitor or BTK inhibitor combination (such as obinutuzumab/ ibrutinib/venetoclax, a BTK inhibitor/venetoclax, or immunochemotherapy) and then moving quickly to an allograft. Chemotherapy is avoided when possible because patients with the TP53 mutation tend to do poorly on this therapy.

BTK Inhibitors in Waldenstrom Macroglobulinemia

Before ibrutinib’s approval and the development of additional BTK inhibitors, first-line treatment for WM was chemotherapy combined with rituximab. Even now, first-line therapy can consist of single-agent rituximab or a combination of bendamustine/rituximab, according to Donnellan. However, clinicians are beginning to reach for BTK inhibitors and BTK combination therapies (ie, ibrutinib and rituximab) for frontline WM patients for ease of administration, improved toxicity profiles over chemotherapies, and reduced risk of flare.

Ibrutinib was approved for the treatment for WM due, in part, to results from the iNNOVATE trial.28 The trial included 150 patients randomized to receive either an ibrutinib/rituximab or placebo/rituximab combination. Results showed a 30-month OS of 94% and 92% with the ibrutinib/rituximab and placebo/ rituximab combinations, respectively. Also, the ORR was 92% with ibrutinib/rituximab versus 47% with placebo/rituximab (P <.001).28 The ibrutinib/rituximab combination showed efficacy even in patients with the MYD88WT gene, a marker of poor ibrutinib response rates and survival outcomes in WM.28 “The MYD88WT patients did pretty well,” Tam mentioned. “So, I think rituximab may be able to rescue some of the wild-type patients.” Tam also commented that immunoglobulin M flare, a rapid increase in monoclonal antibody levels that can occur after rituximab treatment, was rare in the treatment arm.29

Although results in the iNNOVATE trial demonstrated efficacy for the ibrutinib and rituximab combination, Noopur Raje, MD, a professor of lymphoma and myeloma at Harvard Medical School, felt that the biggest issue with data set in the iNNOVATE trial was that there was no ibrutinib monotherapy arm. In clinical practice, he does not combine therapies for patients with WM. Other attendees stated that they use rituximab monotherapy, rituximab/bendamustine combination therapy, or ibrutinib/rituximab combination therapy in first-line treatment of WM. For younger patients, Khan typically does “not use ibrutinib because you must continue them on it forever, whereas drugs like bortezomib or rituximab are extremely well tolerated. You give them a set of 6 cycles and then they are drug-free for a long time.” She added that ibrutinib therapy can be appropriate for some older patients with WM, as long as they don’t have preexisting comorbidities, since “it’s not the easiest drug to tolerate.”

Results from trials testing acalabrutinib and zanubrutinib for patients with WM showed therapeutic promise and limited toxicities. The phase II ACE-WM-001 trial assessed acalabrutinib therapy for 106 patients with treatment-naive or R/R WM.30 The ORR for treatment-naïve patients (n = 14) was 93% (n =13) and for R/R patients (n = 92) it was 94% (n = 86). The PR rates were 71% (n = 10) and 47% (n = 43), respectively. The outcomes were similar to those of ibrutinib, according to Tam. He believes that “acalabrutinib was [not] better than ibrutinib in WM, but maybe better tolerated.”

Zanubrutinib for patients with WM was studied in the phase III ASPEN clinical trial across 2 cohorts. Cohort 1 was composed of patients with treatment-naïve or R/R WM with the MDY88L265P mutation who were randomized to receive either zanubrutinib (n = 102) or ibrutinib (n = 99) with a median follow-up of 19 months, and cohort 2 was composed of patients who had WM with the MDY88WT mutation who received zanubrutinib monotherapy in either setting with a median follow-up of 9.5 months (n = 28).31 Regarding cohort 1, Tam was especially intrigued about the head-tohead comparison of ibrutinib and zanubrutinib. “It’s not about Waldenström,” he commented. “It’s about whether 1 BTK is actually superior to another in a head-to-head study.” He indicated interest in seeing the data, which were cut off in August 2019 and released in December 2019 after the scientific interchange. The 12-month PFS rate was 89.7% (95% CI, 81.7%-94.3%) for the zanubrutinib arm and 87.2% (95% CI, 78.6%-92.5%) for the ibrutinib arm. Grade 3 or higher AE rates were 58.4% and 63.3% in the zanubrutinib and ibrutinib arms, respectively. Zanubrutinib demonstrated clinically meaningful differences, eliciting a higher very good partial response (VGPR) than ibrutinib and showing advantages in tolerability and safety. Although the trial did not meet its primary end point of statistically significant superiority in VGPR rates (zanubrutinib arm [n = 102], 28.4%; ibrutinib arm [n = 99], 19.2%; 2-sided descriptive P = .0921) and CR rates (0 for both arms).31 Results for cohort 2 of the ASPEN trial were presented at the 24th European Hematology Association Congress.32 Overall, zanubrutinib was well tolerated in the patients with the MDY88WT mutation (N = 26). Of the 26, 8 (30.8%) experienced serious AEs, 2 of which were pyrexia. The ORR was 76.9% and the VGPR rate was 15.4%.26 Attendees indicated interest in the safety profile demonstrated by zanubrutinib for WM patients with the wild-type mutation. “There is room for new BTK inhibitors [in WM therapy,] specifically if the therapies work in the wild-type MYD88 population and if they are better tolerated,” said Raje.

Conclusions

The development of BTK inhibitors and other novel treatments has completely changed the management and treatment of mature B-cell lymphomas. According to Barrientos, targeted therapies have become a more viable treatment option for these diseases than traditional therapy. “We are now moving away from chemotherapy,” she said. “We’re mostly going to use targeted biologics for the indolent B-cell malignancies, and there is still room to grow.”

Opportunities for growth exist in several areas, including addressing long-term AEs and overall costs. “BTK inhibitors are interesting,” Raje said, “but they are drugs that have to be used continuously [and] they have associated toxicities.” According to Wierda, having more therapy options does not result in a lower cost of care due to affordability and access challenges, he noted that “one of the challenges we have now…with patients with CLL is being able to get their medications.” For patients with MCL, Kahl noted that the opportunity to achieve “deeper, better-quality remissions” exists. Clinicians are anxious to define the optimal time-limited therapy regimen for patients with CLL. Continued head-to-head comparisons are also imperative in the setting of expanding treatment options, according to Koff. “I think…it’s sometimes difficult to pick the best agent in a crowded field without head-to-head data,” she said. “So [I’m] looking forward to more long-term data in many of these newer agents.”

Despite multiple treatment options, no therapy currently exists to cure patients of mature B-cell lymphomas. Eventually, patients who receive therapy relapse. “A lot of progress has been made [on treatment],” said Donnellan. “And there is still a lot [of progress] to be made in the future.”

References

- Swerdlow SH, Campo E, Pileri SA, et al. The 2016 revision of the World Health Organization classification of lymphoid neoplasms. Blood. 2016;127(20):2375-2390. doi: 10.1182/blood-2016-01-643569.

- Seiler T, Dreyling M. Bruton’s tyrosine kinase inhibitors in B-cell lymphoma: current experience and future perspectives. Expert Opin Investig Drugs. 2017;26(8):909-915. doi: 10.1080/13543784.2017.1349097.

- Jain P, Wang M. Mantle cell lymphoma: 2019 update on the diagnosis, pathogenesis, prognostication, and management. Am J Hematol. 2019;94(6):710- 725. doi: 10.1002/ajh.25487.

- Boukhiar MA, Roger C, Tran J, et al. Targeting early B-cell receptor signaling induces apoptosis in leukemic mantle cell lymphoma. Exp Hematol Oncol. 2013;2(1):4. doi: 10.1186/2162-3619-2-4.

- Zou YX, Zhu HY, Li XT, et al. The impacts of zanubrutinib on immune cells in patients with chronic lymphocytic leukemia/small lymphocytic lymphoma. Hematol Oncol. 2019;37(4):392-400. doi: 10.1002/hon.2667.

- Guo Y, Liu Y, Hu N, et al. Discovery of zanubrutinib (BGB-3111), a novel, potent, and selective covalent inhibitor of Bruton’s tyrosine kinase. J Med Chem. 2019;62(17):7923-7940. doi: 10.1021/acs.jmedchem.9b00687.

- Niemann CU, Herman SE, Maric I, et al. Disruption of in vivo chronic lymphocytic leukemia tumor-microenvironment interactions by ibrutinib— findings from an investigator-initiated phase II study. Clin Cancer Res. 2016;22(7):1572-1582. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-15-1965.

- Owen C, Berinstein NL, Christofides A, Sehn LH. Review of Bruton tyrosine kinase inhibitors for the treatment of relapsed or refractory mantle cell lymphoma. Curr Oncol. 2019;26(2):e233-e240. doi: 10.3747/co.26.4345.

- Akinleye A, Chen Y, Mukhi N, et al. Ibrutinib and novel BTK inhibitors in clinical development. J Hematol Oncol. 2013;6:59. doi: 10.1186/1756-8722-6-59.

- Crisci S, Di Francia R, Mele S, et al. Overview of targeted drugs for mature B-cell non-Hodgkin lymphomas. Front Oncol. 2019;9:443. doi: 10.3389/fonc.2019.00443.

- Brukinsa (zanubrutinib) [prescribing information]: San Mateo, CA: BeiGene USA, Inc; 2019. beigene.com/PDF/BRUKINSAUSPI.pdf.

- Calquence (acalabrutinib) [prescribing information]. Wilmington, DE: AstraZeneca Pharmaceuticals; 2017. azpicentral.com/calquence/calquence.pdf#page=1.

- Imbruvica (ibrutinib) [prescribing information]: Sunnyvale, CA: Janssen Biotech; 2017. imbruvica.com/files/prescribing-information.pdf.

- Kim HO. Development of BTK inhibitors for the treatment of B-cell malignancies. Arch Pharm Res. 2019;42(2):171-181. doi: 10.1007/s12272-019-01124-1.

- Burger JA, Barr PM, Robak T, et al. Long-term efficacy and safety of first-line ibrutinib treatment for patients with CLL/SLL: 5 years of follow-up from the phase 3 RESONATE-2 study [published online October 18, 2019]. Leukemia. doi: 10.1038/s41375-019-0602-x.

- Munir T, Brown JR, O’Brien S, et al. Final analysis from RESONATE: up to six years of follow-up on ibrutinib in patients with previously treated chronic lymphocytic leukemia or small lymphocytic lymphoma. Am J Hematol. 2019;94(12):1353-1363. doi: 10.1002/ajh.25638.

- Varughese T, Taur Y, Cohen N, et al. Serious infections in patients receiving ibrutinib for treatment of lymphoid cancer. Clin Infect Dis. 2018;67(5):687- 692. doi: 10.1093/cid/ciy175.

- Barf T, Covey T, Izumi R, et al. Acalabrutinib (ACP-196): a covalent Bruton tyrosine kinase inhibitor with a differentiated selectivity and in vivo potency profile. J Pharmacol Exp Ther. 2017;363(2):240-252. doi: 10.1124/ jpet.117.242909.

- Byrd JC, Harrington B, O’Brien S, et al. Acalabrutinib (ACP-196) in relapsed chronic lymphocytic leukemia. N Engl J Med. 2016;374(4):323-332. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1509981.

- NCCN Clinical Practice Guidelines in Oncology. B-Cell Lymphomas, version 1.2020. National Comprehensive Cancer Network website. nccn.org/professionals/ physician_gls/pdf/b-cell.pdf. Published January 22, 2020. Accessed February 20, 2020.

- Sharman JP, Banerji V, Fogliatto LM, et al. ELEVATE-TN: phase 3 study of acalabrutinib combined with obinutuzumab (O) or alone versus O plus chlorambucil (Clb) in patients (pts) with treatment-naïve chronic lymphocytic leukemia (CLL). Blood. 2019;134(suppl 1):31. doi: 10.1182/blood-2019-128404.

- Ghia P, Pluta A, Wach M, et al. Acalabrutinib vs rituximab plus idelalisib (IdR) or bendamustine (BR) by investigator choice in relapsed/refractory (RR) chronic lymphocytic leukemia: phase 3 ASCEND study. Hematol Oncol. 2019;37(suppl 2):86-87. doi: 10.1002/hon.54_2629.

- Tam CS, Robak T, Ghia P, et al. Efficacy and safety of zanubrutinib in patients with treatment-naïve chronic lymphocytic leukemia (CLL) or small lymphocytic lymphoma (SLL) with del(l 7p): initial results from arm C of the Sequoia (BGB- 3111-304) trial. Blood. 2019;134(suppl 1):499. doi: 10.1182/blood-2019-125394.

- Cull G, Simpson D, Opat S, et al. Treatment with the Bruton tyrosine kinase inhibitor zanubrutinib (BGB-3111) demonstrates high overall response rate and durable responses in patients with chronic lymphocytic leukemia/small lymphocytic lymphoma (CLL/SLL): updated results from a phase 1/2 trial. Blood. 2019;134(suppl 1):500. doi: 10.1182/blood-2019-125483.

- Rule S, Dreyling M, Goy A, et al. Ibrutinib for the treatment of relapsed/ refractory mantle cell lymphoma: extended 3.5-year follow up from a pooled analysis. Haematologica. 2019;104(5):e211-e214. doi: 10.3324/ haematol.2018.205229.

- Wang M, Rule S, Zinzani PL, et al. Acalabrutinib in relapsed or refractory mantle cell lymphoma (ACE-LY-004): a single-arm, multicentre, phase 2 trial. Lancet. 2018;391(10121):659-667. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(17)33108-2.

- Song Y, Zhou K, Zou D, et al. Safety and activity of the investigational Bruton tyrosine kinase inhibitor zanubrutinib (BGB-3111) in patients with mantle cell lymphoma from a phase 2 trial. Blood. 2018;132(suppl 1):148. doi: 10.1182/blood-2018-117956.

- Dimopoulos MA, Tedeschi A, Trotman J, et al; iNNOVATE Study Group and the European Consortium for Waldenström’s Macroglobulinemia. Phase 3 trial of ibrutinib plus rituximab in Waldenström’s macroglobulinemia. N Engl J Med. 2018;378(25):2399-2410. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1802917.

- Ghobrial I, Fonseca R, Greipp P, et al; Eastern Cooperative Oncology Group. Initial immunoglobulin M ‘flare’ after rituximab therapy in patients diagnosed with Waldenström macroglobulinemia: an Eastern Cooperative Oncology Group Study. Cancer. 2004;101(11):2593-2598. doi: 10.1002/cncr.20658.

- Owen RG, McCarthy H, Rule S, et al. Acalabrutinib monotherapy in patients with Waldenström macroglobulinemia: a single-arm, multicentre, phase 2 study. Lancet Haematol. 2020;7(2):e112-e121. doi: 10.1016/S2352- 3026(19)30210-8.

- Tam C, LeBlond V, Novotny W, et al. A head-to-head phase III study comparing zanubrutinib versus ibrutinib in patients with Waldenström macroglobulinemia. Future Oncol. 2018;14(22):2229-2237. doi: 10.2217/fon-2018-0163.

- Dimopoulos M, Opat S, Lee HP, et al. Major responses in MYD88 wildtype (MYD88WT) Waldenström macroglobulinemia (WM) patients treated with Bruton tyrosine kinase (BTK) inhibitor zanubrutinib (BGB-3111). Presented at: 24th European Hematology Association Congress; June 14, 2019; Amsterdam, the Netherlands. Abstract PF487.

Despite the efficacy of ibrutinib in CLL that was demonstrated in the long-term follow-up of the RESONATE and RESONATE-2 trials, the faculty discussed several safety considerations that guide the selection and management of patients treated with ibrutinib. Across both trials, the rate of atrial fibrillation was 12% in patients with R/R CLL and 16% in the frontline setting. Atrial fibrillation typically occurs early after ibrutinib initiation. Other adverse events (AEs) of special interest include hemorrhage and hypertension. The incidence of major hemorrhage generally is highest in the first 2 years of treatment and decreases thereafter. In the RESONATE-2 trial, over the 5 years of follow-up of patients treated with ibrutinib, the cumulative rate of major hemorrhage increased from 4% at the primary analysis to 11%, and atrial fibrillation increased from 6% to 16%. Of the 9 patients who experienced grade 3 or higher major hemorrhage, 6 were taking concomitant anticoagulation therapy. Hypertension of any grade and of grade 3 occurred in 26% and 9% of patients, respectively.15,16

The RESONATE-2 trial evaluated the efficacy and safety of long-term ibrutinib use in treatment-naïve patients with CLL or SLL, 65 years and older (N = 69). After a median follow-up of 5 years, ibrutinib significantly prolonged progression-free survival (PFS) compared with chlorambucil (median not reached vs 15.0 months; 95% CI, 10.2-19.4), demonstrating an 85% reduced risk for disease progression or death (HR, 0.146; 95% CI, 0.098-0.218).15 According to Tam, based on data from the RESONATE-2 trial, there is a “clear benefit to ibrutinib, not only in terms of PFS, but also for overall survival (OS), which is significant because there is a crossover to ibrutinib for patients on chlorambucil.” The results of the 6-year extended follow-up of the RESONATE trial that were presented at the 2019 ASH Annual Meeting and Exposition demonstrated that extended single-agent ibrutinib treatment yielded sustained efficacy in patients with high-risk R/R CLL or SLL, with PFS significantly longer than that achieved with ofatumumab (HR, 0.148; 95% CI, 0.113-0.196; P <.0001).16