Article

Dr Waun Ki Hong Reflects on Career Milestones in ASCO 2018 Interview

Author(s):

Waun Ki Hong, MD, reflects on his career milestones in head and neck cancer and how his pioneer initiatives continue to make inroads across malignancies.

Waun Ki Hong, MD

Pivotal clinical trials in oncology that laid the groundwork for organ preservation, chemoprevention, and precision medicine can be traced back to pioneering medical oncologist Waun Ki Hong, MD.

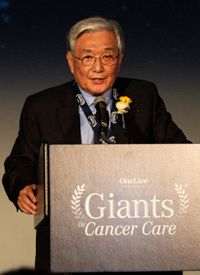

Hong, who was the former head of the Division of Cancer Medicine at The University of Texas MD Anderson Cancer Center, passed away on January 2, 2019. He was most recently recognized by OncLive as the 2018 Giant of Cancer Care® in Head and Neck Cancer.

Throughout his career, Hong held an essential role in the development of larynx-sparing treatments for patients with head and neck cancer through the VA Cooperative Group for Laryngeal Cancer Study, results of which demonstrated that induction chemotherapy and radiation had noninferior survival outcomes to standard laryngectomy and radiation. Additionally, 64% of patients who received chemotherapy had their larynx preserved.1

Additionally, Hong was a senior author on the prospective, randomized BATTLE trial, which demonstrated the feasibility of a biopsy- and biomarker-driven approach for patients with advanced non—small cell lung cancer.2 The late physician also advocated for the development of chemoprevention.

OncLive: You were recognized as a 2018 Giant of the Cancer Care® in Head and Neck Cancer. What does this peer-nominated award mean to you?

You have had a number of notable achievements throughout your career. What stands out to you?

In an interview with OncLive during the 2018 ASCO Annual Meeting, Hong reflected on his career milestones in head and neck cancer and how his pioneer initiatives continue to make inroads across malignancies.Hong: This is a wonderful, incredible honor—something I never expected at all. It was a total surprise. I don’t think I belong in the category of the [Giants of Cancer Care®], and when I received an email [about it], I didn’t believe it. It is such a great honor.I am a first-generation immigrant of this country. I came to this country in 1970 and, in fact, [this year] is 48 years of my immigration to the United States. I have had a wonderful career and started my medicine training at Veterans Affairs (VA) Medical Center in Boston, and then at Memorial Sloan Kettering Cancer Center, where I did my oncology fellowship. Then, I went back to Boston Veterans Administration Medical Center as chief of medical oncology and then moved to The University of Texas MD Anderson Cancer Center in 1984.

When I started my career in mid-1970s at Boston Veterans Administration Medical Center, I ended up seeing a lot of patients with head and neck cancer, especially the patients who had radical surgery and lost their voice box from total laryngectomy. It was really devastating to see that kind of disfiguring in these patients with head and neck cancer.

I was fortunate to have chemotherapy [available] at the time, which was cisplatin and bleomycin and induction chemotherapy followed by radiation treatment. We treated a small number of patients and found [that patients] who had sequential induction chemotherapy followed by radiation achieved excellent local control and, at the same time, spared the larynx. That was a very intriguing finding; many other people observed the same findings.

[We wanted to prove it]; you had to develop a randomized study. One group received the chemotherapy and radiation treatment, and the other group had standard treatment, which was total laryngectomy and radiation. There was a huge challenge, I must tell you, in the late 1970s. I tried to get research grants from the National Cancer Institute (NCI); it failed.

Then, finally, I [began the] VA Cooperative Group for Laryngeal Cancer Study along with my partner Gregory Wolf, MD, who is a head and neck surgeon from the University of Michigan. That proposal was approved with the funding. That was a really dramatic trial initiated in 1980; there were 332 patients [with] 166 patients in each arm. Results showed equal survival [between arms], but the patients who received chemotherapy/radiation treatment had their human voice box spared. This was considered one of the major advances in cancer treatment in the 1990s. That paper was published in 1991 in the New England Journal of Medicine.

That was the organ preservation concept and it expanded to other sites, such as breast conservation in patients with breast cancer, and anus preservation in anal cancer, and bladder conservation in bladder cancer. I was very fortunate to be in the right place and right time, and worked with the right people and, simply, I was very fortunate. That is the larynx preservation concept.

The other [achievement] is called chemoprevention. We focused on understanding the biology process of precancerous cells. We had the idea that we can undermine or suppress the premalignant [cell] in the biology process. We selected patients who presented with oral premalignant lesions and oral leukoplakia. We used retinoid, at the time in 1980, which is a synthetic vitamin A; that was the only agent available at the time. It demonstrated that the premalignant process can be suppressed and delayed.

There has been exciting progress with immunotherapy in head and neck cancer. Could you comment on the evolution of treatment in this area?

Would you like to highlight other research you have been a part of?

[This] was a study that demonstrated the [principle] of chemoprevention, and it is still too early and it’s not really proven yet. However, this approach has huge potential to make an impact in the future, because we understand more biology processes of precancerous lesions. Also, we have some more targeted agents available. Not only that, but we understand more immunology processes of cancer development. If that is so, then we can use this concept of [the cancer being] hijacked by specific targeted agents or immunotherapy agents, so the cancer can be prevented or if not, the cancer process can be delayed. Again, this still has a way to go, but I predict that it’s going to be in clinical practice in the next 10 years.We understand more about the immunological profiling of head and neck tumorigenesis. We understand more about dendritic cell function and T-cell functions. Immunosuppressive agents, immunotherapies such as nivolumab (Opdivo), have been showing some efficacy in patients with recurrent head and neck cancer and that is a really exciting finding.One of the very important things is precision medicine. When we talked about precision medicine in the early 2000s, we had an idea, but [we were] also shooting in the dark. We were again very fortunate to develop the [BATTLE] clinical trial [in lung cancer], which was biopsy-mandated and biomarker-innovated. When we developed that trial in 2003, nobody believed it, and [there was] tremendous skepticism in the cancer community and we had a harder time getting grants.

Finally, we got a grant through the Department of Defense and we conducted and completed the trial of about 220 patients called the BATTLE trial. That was the first biopsy-mandated, biomarker-innovated precision medicine trial in lung cancer. We published a paper on it in 2011 in Cancer Discovery; the editorial of the BATTLE paper was very exciting.

It was a tremendous approach, and that opened up the field of precision medicine. It inspired the NCI to come up with the MATCH trial, so that is the followed concept of the BATTLE trial, [also with the] I-SPY trial with Laura Esserman, MD, in breast cancer. Again, I was very lucky to be part of the BATTLE precision trial at The University of Texas MD Anderson Cancer Center and open the field of precision medicine. I am very proud to be a part of that trial.

References

- Wolf GT, Fisher SG, Hong WK, et al. Induction chemotherapy plus radiation compared with surgery plus radiation in patients with advanced laryngeal cancer. N Eng J Med. 1991;324(24):1685-1690.

- Kim ES, Herbst RS, Wistuba II, et al. The BATTLE Trial: Personalizing Therapy for Lung Cancer [published online ahead of print April 3, 2011]. Cancer Discov. doi: 10.1158/2159-8274.CD-10-0010.