Publication

Article

Beyond the Clinic: Leveraging Research to Tackle Lung Cancer Disparities

Author(s):

Lung cancer remains the most common cause of cancer death in the United States.

NEEL P. CHUDGAR, MD

Lung cancer remains the most common cause of cancer death in the United States. Individuals who identify as Black and/or Hispanic are at even greater risk of mortality. Lung cancer screening (LCS) has been recommended since 2013, but remains underutilized, especially in economic and socially marginalized communities. Incidental lung nodules, commonly found on imaging done for other purposes, such as trauma evaluations, are often diagnosed later as cancers and represent a source of morbidity and mortality.

Many vulnerable groups and marginalized communities receive care in the emergency department setting, where follow-up of incidental nodules is fragmented and incomplete. Low rates of LCS and inappropriate follow-up of incidental pulmonary nodules (IPNs), thus, represent 2 significant drivers of cancer care inequities. Research initiatives aimed towards understanding and combating systemic inadequacies contributing to these inequities have the potential to improve outcomes in populations that are in need.

Addressing Morbidity and Mortality in Minority Populations

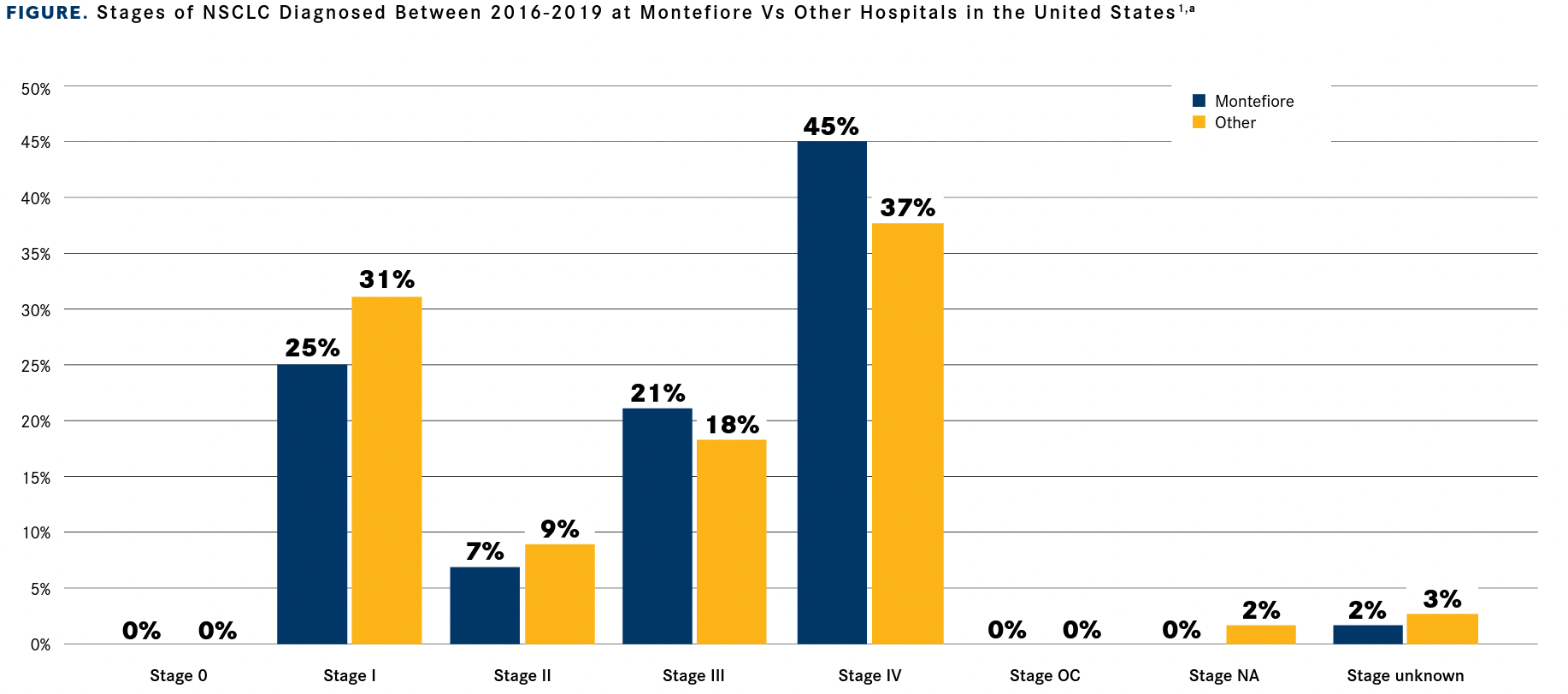

Data from the Commission on Cancer demonstrates a large proportion of individuals diagnosed with non–small cell lung cancer over a 4-year period identified as Black (39%) or Hispanic (33%), compared with 23% who identified as White at the Montefiore Einstein Cancer Center (Montefiore) in the Bronx, New York. These figures are in stark contrast to other New York health care settings, where 81% of patients are White. Our patient population is also more likely to be diagnosed at later stages. When compared with other New York hospitals, the proportion of patients at Montefiore who are diagnosed with stage I lung cancer is markedly lower (25% vs 31%), and the proportion of those with stage IV disease is higher (45% vs 37%) (FIGURE1).

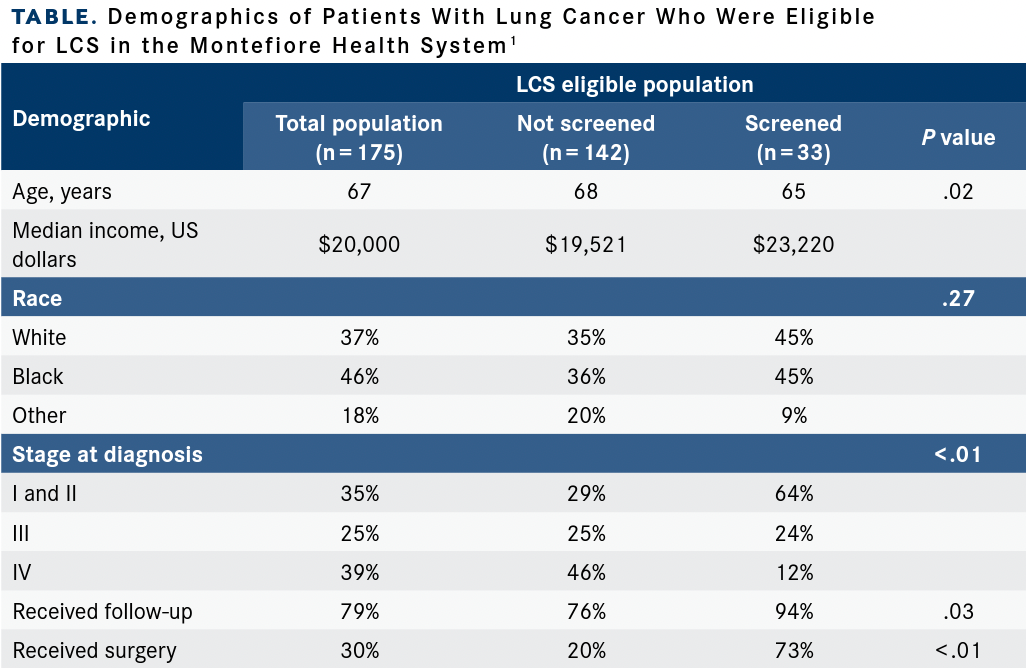

TABLE. Demographics of Patients With Lung Cancer Who Were Eligible for LCS in the Montefiore Health System

Other data from Montefiore have demonstrated additional inequities in patients with primary lung cancers diagnosed between 2013 and 2016. Only 417 (55%) were found in patients with an in-network primary care provider, illustrating the need for a better support system and for a systematic approach to identify and guide these patients. Furthermore, of the 175 of these patients who were eligible for LCS, only 33 had completed appropriate screening. A large proportion of this population with lung cancers that were identified outside of screening was composed of Black (46%) and Hispanic (34%) patients with a median per capita income of approximately $20,000 (TABLE).1

Addressing Inadequacies of Lung Cancer Screening

Screening is particularly challenging in individuals from racial and ethnic minority groups and in those who have been socioeconomically marginalized. For example, of more than 50,000 people enrolled in the seminal National Lung Screening Trial, only 4.5% of participants identified as Black and 1.7% as Hispanic. This is in sharp contrast to the screening population described at our institution.2

FIGURE. Stages of NSCLC Diagnosed Between 2016-2019 at Montefiore Vs Other Hospitals in the United States

More work needs to be done to study and implement LCS in these patient populations. To this end, we have formed a collaboration with the LUNGevity Foundation with the objective of, “Increasing access to lung cancer screening in the Bronx in Latino and African American communities.” Known as Project URBANA, the initiative seeks to increase uptake of, and compliance with, LCS through educational initiatives and engagement with a unique community peer navigation program—the Bronx Oncology Living Daily (BOLD) program. Drawing from the principles of Community-Based Participatory Research, Project URBANA focuses on increasing access to care among African American and Latino community members. At its core, this project is targeted outreach with educational materials developed in partnership with communities with content that is both relevant and language appropriate. This content coupled with trained peer navigators from within the community strives to address social constructs of health care often overlooked in daily practice.

Reducing the Burden of Incidental Pulmonary Nodules

Each year, more than 1.5 million individuals are diagnosed with an IPN.3 Guidelines exist for the follow-up of IPNs; however, treatment adherence is often poor.4 This is especially true in Black and Hispanic populations where approximately 50% of patients are notified of IPNs and have significantly lower rates of adhering to follow-up imaging. This population also has increased odds of delaying follow-up appointments.5

With continued support from LUNGevity, we have devised a multipronged approach to develop an incidental pulmonary nodule management program for our community. Through the incorporation of software to automatically detect notation of lung nodules in radiology reports, we will shift to more active identification of people with concerning nodules who will be proactively referred to our high-risk lung nodule clinic. Individual risk for malignancy will be evaluated using artificial intelligence–based calculators derived from the electronic medical record to facilitate guideline concordant care.

Finally, we will evaluate a blood-based cancer biomarker to further risk stratify patients and will prospectively apply it to individuals already enrolled in our nodule clinic. Our overall objective is to facilitate earlier diagnosis of lung cancer in our community and decrease risk of advanced disease and death.

Translating Advocacy into Action

Research initiatives provide us with the ability to advocate for historically marginalized people by generating hypotheses that seek to increase knowledge of inequities of care. Studies focusing on implementation of care in the setting of racial and ethnic inequities are critically needed.

Deficiencies in lung cancer care are multifactorial, and occur at the levels of screening, diagnosis and management. Through research that incorporates culturally sensitive patient navigation, use of available technologies and a multidisciplinary approach to patient care, there are significant opportunities to improve screening, cancer care, and outcomes for everyone.

References

- Su CT, Bhargava A, Shah CD, et al. Screening patterns and mortality differences in patients with lung cancer at an urban underserved community. Clin Lung Cancer. 2018;19(5):e767-e773. doi:10.1016/j.cllc.2018.05.019

- National Lung Screening Trial Research Team; Aberle DR, Adams AM, Berg CD, et al. Reduced lung-cancer mortality with low-dose computed tomographic screening. N Engl J Med. 2011;365(5):395409. doi:10.1056/NEJMoa1102873

- Gould MK, Tang T, Liu IL, et al. Recent trends in the identification of incidental pulmonary nodules. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2015;192(10):1208-1214. doi:10.1164/rccm.201505-0990OC

- Farjah F, Monsell SE, Gould MK, et al. Association of the intensity of diagnostic evaluation with outcomes in incidentally detected lung nodules. JAMA Intern Med. 2021;181(4):480-489. doi:10.1001/ jamainternmed.2020.8250

- Schut RA, Mortani Barbosa EJ Jr. Racial/ethnic disparities in follow-up adherence for incidental pulmonary nodules: an application of a cascade-of-care framework. J Am Coll Radiol. 2020;17(11):1410-1419. doi:10.1016/j.jacr.2020.07.018