A Discussion on the Study 309/KEYNOTE-775 Data

Key opinion leaders discuss the presented data from Study 309/KEYNOTE-775, highlighting patient reported outcomes, safety, and dosing.

Episodes in this series

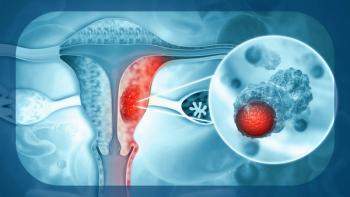

Bradley Monk, MD, FACOG, FACS: You talked about the MSI [microsatellite instability]–high group. We’ve talked about this before. Remember that we led heterogeneity. Are all patients with MSI-high created equally, or is there a difference between the genetically mutated—somatic or germline—vs the epigenetic loss? You would think that the patients with epigenetic loss would benefit less than the patients who are genetically mutated and getting germline or somatic mutations. Is that true?

Vicky Makker, MD: You bring up a good point. With regard to whether that holds true for this regimen, we need greater experience, and we need to do the correlative studies to drill down to see if that, indeed, holds true with this combination.

Bradley Monk, MD, FACOG, FACS: The point is that if pembrolizumab doesn’t really work that well for patients with epigenetic loss, MSI high is the most common subgroup for whom there might be the opportunity to add lenvatinib. On the other hand, if you have true genetic mutated loss like what you get in germline or somatic mutations like BRCA, which is sort of analogous to HRD [homologous recombination deficient], then pembrolizumab is enough. Do you think there’s an opportunity to explore that?

Vicky Makker, MD: There’s absolutely an opportunity to explore that. That’s certainly 1 of the points that’s going to be explored as we do the correlative and end point analysis for this study. We’re also hoping to share with everyone similar analyses that were done on KEYNOTE-146 that hopefully speak to that.

Bradley Monk, MD, FACOG, FACS: I love it. I want to get others involved. I want to ask another thing. We were a little surprised. Generally, when we give these presentations, we give the PROs [patient-reported outcomes] at the same time. Certainly, if it’s a curative regimen, we say that you have to be alive to have a decreased experience. But in a setting where it’s purely palliative, we didn’t hear patient-reported outcomes. Tell us about what the patient experience is or what it means because PFS [progression-free survival] is a change in the CT scan. OS [overall survival] is really meaningful, but at what cost? We’re going to get to the adverse effects [AEs] in a minute. Tell me about the patient experience, which we can’t lose.

Vicky Makker, MD: With regard to your questions about the PROs, you’re absolutely correct. That is a very meaningful end point. Ketta will be leading the presentation. She can speak more to this than I can.

Bradley Monk, MD, FACOG, FACS: Let’s let her talk.

Vicky Makker, MD: Absolutely.

Bradley Monk, MD, FACOG, FACS: I didn’t know that. It’s not surprising because you are the experts. Ketta, tell us about this patient experience situation with a regimen that, quite frankly, is more toxic but you live longer. Go ahead, Ketta.

Domenica Lorusso, MD, PhD: You will see where the poster has been accepted at the next ASCO [American Society of Clinical Oncology] Annual Meeting. I cannot spoil it, but you will see. It’s a surprise that in front of this toxicity, you’ll be surprised about the PRO data.

Bradley Monk, MD, FACOG, FACS: I don’t think I will be because I’m a big fan of this. Dave, go ahead.

David O’Malley, MD: Brad, I have to challenge you here. You continue to say that this is just palliative therapy. We’re still in this short follow-up period, but at 2 years, we have 20% to 30% of patients who have not recurred.

Bradley Monk, MD, FACOG, FACS: There’s a tail?

David O’Malley, MD: There are tails there. We have a CR [complete response] rate of 5%.

Vicky Makker, MD: That’s right.

David O’Malley, MD: We may be curing patients. I can tell you, we’re not doing that with standard cytotoxic chemotherapy.

Bradley Monk, MD, FACOG, FACS: Thank you for that.

David O’Malley, MD: Let’s not throw those terms around so quickly until we have more mature data.

Bradley Monk, MD, FACOG, FACS: Lovely, thank you. Nicoletta, do you have any experience with this regimen?

Nicoletta Colombo, MD, PhD: Oh yes.

Bradley Monk, MD, FACOG, FACS: Tell us about the adverse-effect profile and what you’ve learned about how to mitigate it and help patients.

Nicoletta Colombo, MD, PhD: There are adverse effects, that’s for sure. A majority of the adverse effects are probably related to lenvatinib more than pembrolizumab, although pembrolizumab also has adverse effects. For sure, we have to learn how to manage lenvatinib toxicity particularly. There’s always a question about the initial dose of lenvatinib, which many physicians perceive as being too high. Therefore, of course, the question is always about whether we can we start with a lower dose and achieve the same results because this is the main issue. Apparently, there are data from other diseases telling us that this is not the case, such that you may need a higher dose to start that may be decreased based on the toxicity that you observed. This is a pity because, of course. It will be much nicer to start at the lower dose and not to be able to avoid the toxicity that was observed, but apparently this is not possible.

You have to be prepared. Surely, there are toxicities that we’re used to treating. There are also others that are a bit different, particularly for gynecologic oncologists, because we are more used to chemotherapy and not to these agents. It’s important to learn because this regimen is very active. I foresee the use of this regimen more in the future, so we have to find a way to make it manageable, acceptable, and usable for the majority of patients who may benefit from them.

Bradley Monk, MD, FACOG, FACS: The challenge has been that people look at dose interruption or dose reduction as failure. It’s not failure. We interrupt and dose reduce routinely basically in every regimen we use. The challenge is that this is really 3 agents in q, even though it’s 2. The first is I/O [immuno-oncology], and we all know how to manage immune-related adverse reactions, No. 1. The second is the anti-VEGF effect, which is hypertension, and it can happen very quickly. No. 3, the oral anticancer therapies are again something we’re very familiar with, particularly in the PARP world. The oral administration causes GI [gastrointestinal] disturbances and fatigue.

You have I/O, VEGF, and oral GI disturbances and fatigue. If you put all that together and already know how to do each of them individually, then we can get through it understanding that dose interruptions and dose reductions are not failures. The good news is that, as you said, if it’s lenvatinib, then you’re right. If you interrupt it, the adverse reactions go away in a day or 3. This is the whole PARP epiphany: You don’t get a dose and suffer through it for a 3-week cycle. If you’re nauseated from a PARP inhibitor, you stop, and then you’re not nauseated the day after tomorrow. Vicky, to address this, what’s the right dose?

Vicky Makker, MD: We now have a phase 1b/2 trial and a phase 3 trial that have evaluated lenvatinib at 20 mg orally as the starting dose. We have a lot of prospective data regarding that starting dose, and we’re going to learn more as patients are on follow-up. I agree with Nicoletta completely, which is that we have to learn how to manage the AE profile of this drug, specifically the lenvatinib. However, the AEs are consistent with what we see with other VEGF TKIs [tyrosine kinase inhibitors]. This is a class effect. You’re right. It’s par for the course to start at the dose that is recommended and then routinely dose hold and dose reduce as is medically indicated.

What’s helpful with this regimen, though, is to understand that it’s important to maximize supportive care to ensure that patients are ideally prehabilitated. You’re going to start this regimen at some point soon, so make sure their blood pressure is optimally controlled, make sure they’re checking their blood pressures at home, and ensure that their nausea, weight—and things like this that can be controlled—are stable and that they’re in good regimens. Refer them to the nutritionist if you need to. Things of this nature maximally support the patient. See the patient frequently because you know what’s coming. This is preferably weekly for the first 2 or 3 cycles because we know that most of the adverse effects tend to occur earlier in the course of therapy, not that your attention can wane over time, but most of them occur early. Then, ensure that the patient is well-educated and understands what’s potentially going to happen in terms of the adverse events and how they’re going to manage them. Ensure them that the entire clinical team, the nurses, the PAs [physician assistants], etc. are also well-versed in the regimen. That goes a long way in helping the patient have a better experience and helps everyone feel more confident as we gain more experience.

Transcript Edited for Clarity